Photon

| Composition | Elementary particle |

|---|---|

| Statistics | Bosonic |

| Interactions | Electromagnetic, Weak, Gravity |

| Symbol | γ |

| Theorized | Albert Einstein |

| Mass | 0 < 1×10−18 eV/c2 [1] |

| Mean lifetime | Stable[1] |

| Electric charge | 0 < 1×10−35 e[1] |

| Spin | 1 |

| Parity | −1[1] |

| C parity | −1[1] |

| Condensed | I(JPC)=0,1(1−−)[1] |

The photon is a type of elementary particle, the quantum of the electromagnetic field including electromagnetic radiation such as light, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force (even when static via virtual particles). The photon has zero rest mass and always moves at the speed of light within a vacuum.It is simply known as "spark of Light"

Like all elementary particles, photons are currently best explained by quantum mechanics and exhibit wave–particle duality, exhibiting properties of both waves and particles. For example, a single photon may be refracted by a lens and exhibit wave interference with itself, and it can behave as a particle with definite and finite measurable position or momentum, though not both at the same time. The photon's wave and quantum qualities are two observable aspects of a single phenomenon – they cannot be described by any mechanical model;[2] a representation of this dual property of light that assumes certain points on the wavefront to be the seat of the energy is not possible. The quanta in a light wave are not spatially localized.

The modern concept of the photon was developed gradually by Albert Einstein in the early 20th century to explain experimental observations that did not fit the classical wave model of light. The benefit of the photon model was that it accounted for the frequency dependence of light's energy, and explained the ability of matter and electromagnetic radiation to be in thermal equilibrium. The photon model accounted for anomalous observations, including the properties of black-body radiation, that others (notably Max Planck) had tried to explain using semiclassical models. In that model, light was described by Maxwell's equations, but material objects emitted and absorbed light in quantized amounts (i.e., they change energy only by certain particular discrete amounts). Although these semiclassical models contributed to the development of quantum mechanics, many further experiments[3][4] beginning with the phenomenon of Compton scattering of single photons by electrons, validated Einstein's hypothesis that light itself is quantized.[5][6] In 1926 the optical physicist Frithiof Wolfers and the chemist Gilbert N. Lewis coined the name "photon" for these particles.[7] After Arthur H. Compton won the Nobel Prize in 1927 for his scattering studies,[8] most scientists accepted that light quanta have an independent existence, and the term "photon" was accepted.

In the Standard Model of particle physics, photons and other elementary particles are described as a necessary consequence of physical laws having a certain symmetry at every point in spacetime. The intrinsic properties of particles, such as charge, mass, and spin, are determined by this gauge symmetry. The photon concept has led to momentous advances in experimental and theoretical physics, including lasers, Bose–Einstein condensation, quantum field theory, and the probabilistic interpretation of quantum mechanics. It has been applied to photochemistry, high-resolution microscopy, and measurements of molecular distances. Recently, photons have been studied as elements of quantum computers, and for applications in optical imaging and optical communication such as quantum cryptography.

Contents

- 1Nomenclature

- 2Physical properties

- 3Historical development

- 4Einstein's light quantum

- 5Early objections

- 6Wave–particle duality and uncertainty principles

- 7Bose–Einstein model of a photon gas

- 8Stimulated and spontaneous emission

- 9Second quantization and high energy photon interactions

- 10The hadronic properties of the photon

- 11The photon as a gauge boson

- 12Contributions to the mass of a system

- 13Photons in matter

- 14Technological applications

- 15Recent research

- 16See also

- 17Notes

- 18References

- 19Additional references

- 20External links

Nomenclature[edit]

The word quanta (singular quantum, Latin for how much) was used before 1900 to mean particles or amounts of different quantities, including electricity. In 1900, the German physicist Max Planck was studying black-body radiation: he suggested that the experimental observations would be explained if the energy carried by electromagnetic waves could only be released in "packets" of energy. In his 1901 article [9] in Annalen der Physik he called these packets "energy elements". In 1905, Albert Einstein published a paper in which he proposed that many light-related phenomena—including black-body radiation and the photoelectric effect—would be better explained by modelling electromagnetic waves as consisting of spatially localized, discrete wave-packets.[10] He called such a wave-packet the light quantum (German: das Lichtquant).[Note 1] The name photon derives from the Greek word for light, φῶς (transliterated phôs). Arthur Compton used photon in 1928, referring to Gilbert N. Lewis.[11] The same name was used earlier, by the American physicist and psychologist Leonard T. Troland, who coined the word in 1916, in 1921 by the Irish physicist John Joly, in 1924 by the French physiologist René Wurmser (1890–1993) and in 1926 by the French physicist Frithiof Wolfers (1891–1971).[7] The name was suggested initially as a unit related to the illumination of the eye and the resulting sensation of light and was used later in a physiological context. Although Wolfers's and Lewis's theories were contradicted by many experiments and never accepted, the new name was adopted very soon by most physicists after Compton used it.[7][Note 2]

In physics, a photon is usually denoted by the symbol γ (the Greek letter gamma). This symbol for the photon probably derives from gamma rays, which were discovered in 1900 by Paul Villard,[12][13] named by Ernest Rutherford in 1903, and shown to be a form of electromagnetic radiation in 1914 by Rutherford and Edward Andrade.[14] In chemistry and optical engineering, photons are usually symbolized by hν, which is the photon energy, where h is Planck constant and the Greek letter ν (nu) is the photon's frequency.[15] Much less commonly, the photon can be symbolized by hf, where its frequency is denoted by f.

Physical properties[edit]

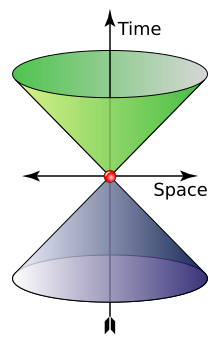

A photon is massless,[Note 3] has no electric charge,[16] and is a stable particle. A photon has two possible polarization states.[17] In the momentum representation of the photon, which is preferred in quantum field theory, a photon is described by its wave vector, which determines its wavelength λ and its direction of propagation. A photon's wave vector may not be zero and can be represented either as a spatial 3-vector or as a (relativistic) four-vector; in the latter case it belongs to the light cone (pictured). Different signs of the four-vector denote different circular polarizations, but in the 3-vector representation one should account for the polarization state separately; it actually is a spin quantum number. In both cases the space of possible wave vectors is three-dimensional.

The photon is the gauge boson for electromagnetism,[18]:29–30 and therefore all other quantum numbers of the photon (such as lepton number, baryon number, and flavour quantum numbers) are zero.[19] Also, the photon does not obey the Pauli exclusion principle.[20]:1221

Photons are emitted in many natural processes. For example, when a charge is accelerated it emits synchrotron radiation. During a molecular, atomic or nuclear transition to a lower energy level, photons of various energy will be emitted, ranging from radio waves to gamma rays. Photons can also be emitted when a particle and its corresponding antiparticle are annihilated (for example, electron–positron annihilation).[20]:572,1114,1172

In empty space, the photon moves at c (the speed of light) and its energy and momentum are related by E = pc, where p is the magnitude of the momentum vector p. This derives from the following relativistic relation, with m = 0:[21]

The energy and momentum of a photon depend only on its frequency (ν) or inversely, its wavelength (λ):

where k is the wave vector (where the wave number k = |k| = 2π/λ), ω = 2πν is the angular frequency, and ħ = h/2π is the reduced Planck constant.[22]

Since p points in the direction of the photon's propagation, the magnitude of the momentum is

The photon also carries a quantity called spin angular momentum that does not depend on its frequency.[23] The magnitude of its spin is √2ħ and the component measured along its direction of motion, its helicity, must be ±ħ. These two possible helicities, called right-handed and left-handed, correspond to the two possible circular polarization states of the photon.[24]

To illustrate the significance of these formulae, the annihilation of a particle with its antiparticle in free space must result in the creation of at least two photons for the following reason. In the center of momentum frame, the colliding antiparticles have no net momentum, whereas a single photon always has momentum (since, as we have seen, it is determined by the photon's frequency or wavelength, which cannot be zero). Hence, conservation of momentum (or equivalently, translational invariance) requires that at least two photons are created, with zero net momentum. (However, it is possible if the system interacts with another particle or field for the annihilation to produce one photon, as when a positron annihilates with a bound atomic electron, it is possible for only one photon to be emitted, as the nuclear Coulomb field breaks translational symmetry.)[25]:64–65 The energy of the two photons, or, equivalently, their frequency, may be determined from conservation of four-momentum. Seen another way, the photon can be considered as its own antiparticle. The reverse process, pair production, is the dominant mechanism by which high-energy photons such as gamma rays lose energy while passing through matter.[26] That process is the reverse of "annihilation to one photon" allowed in the electric field of an atomic nucleus.

The classical formulae for the energy and momentum of electromagnetic radiation can be re-expressed in terms of photon events. For example, the pressure of electromagnetic radiation on an object derives from the transfer of photon momentum per unit time and unit area to that object, since pressure is force per unit area and force is the change in momentum per unit time.[27]

Each photon carries two distinct and independent forms of angular momentum of light. The spin angular momentum of light of a particular photon is always either +ħ or −ħ. The light orbital angular momentum of a particular photon can be any integer N, including zero.[28]

Experimental checks on photon mass[edit]

Current commonly accepted physical theories imply or assume the photon to be strictly massless. If the photon is not a strictly massless particle, it would not move at the exact speed of light, c, in vacuum. Its speed would be lower and depend on its frequency. Relativity would be unaffected by this; the so-called speed of light, c, would then not be the actual speed at which light moves, but a constant of nature which is the upper bound on speed that any object could theoretically attain in spacetime.[29] Thus, it would still be the speed of spacetime ripples (gravitational waves and gravitons), but it would not be the speed of photons.

If a photon did have non-zero mass, there would be other effects as well. Coulomb's law would be modified and the electromagnetic field would have an extra physical degree of freedom. These effects yield more sensitive experimental probes of the photon mass than the frequency dependence of the speed of light. If Coulomb's law is not exactly valid, then that would allow the presence of an electric field to exist within a hollow conductor when it is subjected to an external electric field. This thus allows one to test Coulomb's law to very high precision.[30] A null result of such an experiment has set a limit of m ≲ 10−14 eV/c2.[31]

Sharper upper limits on the speed of light have been obtained in experiments designed to detect effects caused by the galactic vector potential. Although the galactic vector potential is very large because the galactic magnetic field exists on very great length scales, only the magnetic field would be observable if the photon is massless. In the case that the photon has mass, the mass term 12m2AμAμ would affect the galactic plasma. The fact that no such effects are seen implies an upper bound on the photon mass of m < 3×10−27 eV/c2.[32] The galactic vector potential can also be probed directly by measuring the torque exerted on a magnetized ring.[33] Such methods were used to obtain the sharper upper limit of 10−18 eV/c2 (the equivalent of 1.07×10−27 atomic mass units) given by the Particle Data Group.[34]

These sharp limits from the non-observation of the effects caused by the galactic vector potential have been shown to be model-dependent.[35] If the photon mass is generated via the Higgs mechanism then the upper limit of m ≲ 10−14 eV/c2from the test of Coulomb's law is valid.

Photons inside superconductors do develop a nonzero effective rest mass; as a result, electromagnetic forces become short-range inside superconductors.[36]

No comments:

Post a Comment